Part One

I can sometimes hear them as I drive around the sharp bend in the busy suburban road, almost always at sundown. They’re so close, they seem to be right behind the chain-link fence: a whole pack of hairy, ravenous creatures – so starved they sound like they’re trying to eat one another. I would guess there was at least a couple dozen, all huddled inside of a small den surrounded by hundreds of mangled animal carcasses. Which one is the weakest? The one with the gauntest skeleton? That poor selected member of the clan that has no other purpose now but to provide a small meal to its siblings?

The monstrous howl is unsteady, making it more unnerving to the ears. As its about to stop, the next creature finds its turn, and then more join in the chorus. Much to the pleasure of all local ghouls and vampires, this keeps the song going for a while longer. Or maybe they also howl as a sort of prayer, seeking to stave off a moonlight that brings with it a coldness that’s felt hard against their frail bodies. I ask myself these questions, each one forming a more perfect image in my mind, before reflecting on my losses.

Nowadays, whenever I have found myself on that trail during a mid-evening walk, and the howling begins, I resolve to head back to the car. I know that the creatures are actually some ways beyond the fence, somewhere in the hills, up from the horse trail but below the expensive houses. But they are not afraid of the daylight, emerging daily from the dark trees and the dry trails so as to begin the mortal struggle of finding sustenance.

This hunger comes with a cost to local communities. Wikipedia informs that some zoologists refer to them as the “American jackal.” In the outer eastern suburbs of Los Angeles County, somewhat south of the national forest, they are seen by me as a menace that will kidnap and kill and consume your beloved pets. For others – more than you would guess – an encumbered quadruped that requires all the sympathy and protection that can be given to it.

Those damn coyotes!

I wish I could say that my experience with these carnivores came only from reading Wikipedia entries. But we’ve always had dogs in our family. In the evenings, after it has finally cooled down, I would take my two bite-sized pets on a local tour around a half dozen parks, where the three of us can practice the subtle art of leashlessness. Occasionally – at least half the time – a couple cold cans of cheap domestic lager get involved. The two small dogs run and shit and wear themselves out while I slug the beer and walk slowly around the perimeter. They’re never more than 20 feet in front of me. Maybe a little further. Never less than that.

Fine, there is something that needs to be confirmed as true: sometimes I couldn’t even see them. In a metropolis, the most pastoral scene to which one can bear witness to is the sight of one’s dogs dashing across the vibrant green lawn just as the pink sky begins its half-hour reign over the horizon. We’re all just trying to keep in good health, anyway.

My television hero, Al Bundy, envied the simple-if-slovenly lifestyle of the average household mutt. Primal instincts are all that’s expected, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. No debt or mortgage; no need to learn a new skill for a bigger paycheck that allows for one more meal and month of rent. None of that.

One hears about “fish out of water,” but that is an imperfect analogy: the fish quickly dies. Jaws does not grow wings and continue its hunt after it’s taken out of the ocean. The tourist – the man out of his element – while still making erratic movements, eventually finds the airport. He still functions with the only intelligence he knows. This is true also of the bloodthirsty beast with four legs. The stomach of a displaced predator continues to growl, and they can’t walk up to the sandwich man to make it stop.

With some similarity, domesticated pets are also dependent on he who wields the meat. They learn this. Chasing the resident cats and squirrels are mere pastimes, not necessary actions. And that’s what can never be reconciled, not between man or pet or predator. The door and the dog food must be opened and given by me. No responsibility can be granted for them to make that decision. However flimsily, this has been my reasoning for “leashlessness”: if I can liberate my dogs from the tyrannical leash for even fifteen or twenty minutes a day, I will do that. I, the ordinary abstractionist, the only one who can agitate for civil rights, makes that decision for them. It is left up to every thinking person to acknowledge, and affirm as law, that I am the one who chooses to grant my duly owned animals that pleasure. If they get into a fight with another dog – what should be the chief concern – then I would cross that bridge if and when it happens.

Prior to the first attack, I had not been aware that leashlessness would warrant any more worry aside from that just stated. Perhaps that’s because, in the strange parts of the world where I live, “coyote killed by man” might very well proliferate headlines almost as quickly as “man killed by coyote.” Despite California being the state with the most severe coyote problem (something I would soon learn), I failed to realize that few other Californians seemed to be aware of this.

There’s a horse trail in our county, in San Dimas. I’ve been hiking it since my family first moved here. I take my dogs to this trail and let them run free. A few years ago, we decided to adopt a rescue dog. We named her Sydney, a small black female that we figured was bred to breed, as her teats were tattered and cracked. We gave her a good home: cool air conditioning, large slices of cheese, and evening walks. She was to be the mate of my other dog, Buster, an adventurous Chihuahua/miniature-terrier mutt, who we had owned for about a year. Sydney’s new household brought newfound freedom, and she relished in it. I’d call her name and she’d dart from one room into my bed, headfirst and on her back, ready for belly-rubs.

For all this time, at this horse trail and at others, Buster and I had been taking our leashless walks. All canine, Buster likes to chase squirrels and rabbits, pursuing his antagonists off the trail and up into the bushes and trees. Sydney quickly adopted his habits, running behind him into the brush. We tackled this trail many times without incident.

One day, we had one. It was a warm, ordinary day. We were not far from the parking lot. Spotting a spry rodent, Buster set off after it. Sydney followed him. The large brush is just off to the side of the trail. Buster disappeared into it; Sydney too. I called for them. Buster came jumping out, as he’s done a million times before. Then I heard it. The sharp squeal. Only a single one. Screaming her name, I ran up into the brush. No predator, no prey. I neither saw, nor heard, anything at all. I leash Buster and take him up the hillside, still yelling. Nothing. Like she was never even there. Two months we had her, and she was taken in two seconds; twenty feet from me, and maybe 250 from the car.

I found a few articles online that confirmed the coyote presence. The lesson was mine to be learned. If I wanted to keep Buster alive, as well as any other future pet, I could no longer let them run as far away from me as they wanted. So, I capitulated, and Buster became an indoor dog that occasionally went for walks around the mobile home park. It was like this for a while, and my dog hated this change, showing this by whining or pawing at my leg when the evenings came and went.

Early 2013: my friend calls me up. He said that his family had picked up a stray puppy near their house and would I be willing to offer it a home? I said maybe; I had to ask my family. I came by one afternoon. Inside of a hot, cramped backroom was a small male dog with puffy jet black hair, which was anchored to a weight set with a short leash. “Cupcake” could not have been more than a year old, and probably less than that. My friend said that he had been like this for several months now; little movement allowed to it.

The dog came home with me that day. We quickly gave him a more fitting name: “Shadow.” For some time after that, we’d refer to this dog as a “rescue” – making us all feel more heroic about the adoption. Shadow took to his new home right way. The cheesy snacks and air-conditioned room and the comfortable bed – these all made a gleaming look appear in his bright eyes that reminded us of his appreciation. The two dogs became pals. Shadow looked at Buster as if he was something of a hero, following him around the house and getting into the habit of chewing on his ears and playfully pouncing on him.

But I knew that a new friend was not enough for Buster. He was missing his leashless walks. For him, the leash was intolerable, and he would choke himself by pulling incessantly, which made the walks far less pleasurable. No retraining him at this point. He was accustomed to the free running of his earliest days. His sad stares and pensive pawing had finally gotten my attention. It wasn’t long after we had adopted Shadow that I resolved to once again practice leashlessness. We’d only go to the local parks and schools, the latter in the afterhours. I’d make sure they were no more than 30 feet from me, always in the line of sight. No coyote would attack us at these times and with these precautions, I believed. With this slight modification, our exercise could resume.

Sometimes we’d go back to that horse trail – leashes worn! On at least two occasions, walking later in the day, we heard the coyote song emanating from the unseen hillside. Others could be seen scurrying up the hills, beyond the “private property” fencings. One time, in the middle of the day, a very brave coyote followed us all the way back to our car. Buster saw it, and wanted to confront it, but I held tight and yelled at our stalker, which kept its distance at about forty feet. The coyote watched as we got in the car and drove away. They don’t attack humans, it seems. Or do they? For the most part, I decided to keep our walking contained to the local parks.

This worked for nearly five years. My dogs maintained healthy weights and slept well. But I must have grown careless in this routine. September, 2017: It was later than our usual time, sometime around 9 PM. I took the dogs to a local park, if only to do a couple laps around the track. I was walking around the large patch of green grass, my headphones in, and the dogs just off to the side of me.

I make my way off the dirt trail and start to walk across the lawn to the other side. Buster came up in front of me. About half way across, and I notice his absence. I take the earbuds out and look to where we all just were, now some-fifty feet away. I don’t see the other one. Shadow is gone. I call loudly for him. He doesn’t come. Buster and I stood silent on the grass for five, long, agonizing seconds – which was more than enough time to realize the repeated error that was mine to live with yet again. Then we heard it on the opposite side of the wash: the faint and painful squealing of my pet-turned-prey.

Buster and I become lightning bolts. We sprint to the picnic tables, where I assume to be the source of Shadow’s yelping. The park lights are lackluster, making it very dark near these tables. I can hardly see anything. In the hysteria, I neglect to leash Buster, and so I must keep him close while screaming and looking for Shadow, hoping that he hasn’t been carried off yet by a lurking predator that I know is navigating the nightfall better than I. The only light I have is on my IPhone, which I’m frantically trying to turn on. I’m scanning for Shadow’s body in the darkness, moving away from the tables a bit and down towards the flower bed where there appears to be more light. By now, I’ve managed to get the leash on Buster.

Then I turn and look back up at the tables, and that’s when I see it – the largest one I’ve ever encountered. The menacing figure of scraggly fur and with two glowing eyes that pierce me from 40 feet away – it startles me momentarily. It stands motionless, thinking of its next move. But there’s a small relief: it’s mouth is empty! Despite its size, the weight of Shadow’s body and the urgency of having to move him quickly as we approached – this must have made the creature tired. I run up to it, yelling and flailing my arms. Properly intimidated, it moves in the direction of the parking lot. When I believe it to be gone, I resume my search for Shadow. Circling the tables and flower beds, I can’t find him.

But the predator is not leaving without its meal. Another gaffe! Spinning around, I see that the creature has returned, and this time I see Shadow’s limp body in its mouth. I had run right past Shadow! The coyote is running across the parking lot, intending to cross the street and then up another street, eventually going into the hills, and where dinner – my dog – will be served to the pack.

Buster and I again make chase, running as fast as I can and yelling just as loudly. I stop at the edge of the parking lot, with the streetlights giving me much better illumination. I look and see the coyote on the opposite sidewalk. Its mouth is empty again, and I see no body there or on the road. A few cars pass, creating something of a sporadic barrier. Seeing this as a brief victory, I now breathe heavily and look for Shadow, who I am sure has been dropped somewhere between the dark picnic tables and the bright sidewalk. I call a family member for help. While on the phone, I spot my dog. He was laying in the dirt patch, near the sidewalk. He was bloody but breathing, and not moving.

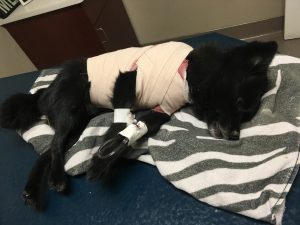

My uncle came. I scooped Shadow up in a towel and the four of us drove to an emergency pet hospital in Diamond Bar. There, Shadow was bandaged and given some fluids. One-thousand dollars for this and for X-rays, which showed seven broken ribs. If he made it through the night, we were told, a team would have to come out and reconstruct his insides. “What do you think,” I ask the veterinarian. “About a fifty-fifty chance?” She said that sounded about right. We left Shadow at the hospital and went home. If the prognosis took a turn for a worse, I would get a phone call.

Trying to forego my typical pessimism, I told my folks that I believed Shadow would live. “I want to try and be optimistic, for once in my life,” I recall saying. I got a call in the middle of the night, somewhere around 2 AM. “Mr. Patten?” asked the lady over the phone. No need: I knew. “Yeah…” I replied sadly and knowingly. “I’m so sorry. Shadow didn’t make it.” As the tears started to form, I thought: Yeah. Me too.

great work sir!